With no budget and no real oversight to develop a digital camera prototype, Sasson again began scrounging for parts at Kodak. “I was just curious to build this thing,” he said.

Despite the novelty of his invention, Sasson said he faced a fair amount of resistance within the Kodak company. He faced both technical and cultural barriers to producing digital cameras for the broader population.

“Photography was really pretty good,” he said. “So if you are going to replace the technology with something new, you have to meet all the attributes of the existing technology and then exceed it.”

When he faced resistance at Kodak, Sasson said it was curiosity and a good sense of humor that kept him going, even while those above him questioned whether his invention would ever be successful. Those two traits, he said, are the most important qualities up-and-coming innovators and entrepreneurs can possess.

“Quite frankly, curiosity will drive you, and a sense of humor will pick you up when you fail,” Sasson said. “And you will be doing that a lot.”

Sasson spent decades—and the majority of his career at Kodak—perfecting the prototype for the first digital camera. More than the technical skills he had from years of experimenting on his own and in school, Sasson said it was the “soft skills” he learned that helped him deal with pushback he received when he first tried to pitch his idea.

“I made just about every mistake there is … about trying to convince people that your idea may be worth pursuing, even though you don’t have enough data to support it at the moment, [and] that the idea you have is not an attack on the culture of the institution,” Sasson said. “It is very important how you relate as a human being. How patient you are with people, how persuasive you are with your idea goes a much longer way toward the initial acceptance. These are all the techniques you use to get your idea moving inside an enterprise.”

Despite apprehension from leaders within the company, Kodak continued to let Sasson further develop his prototype. By 1989, he and a colleague had developed a fully functional digital camera. At that time, he said, the struggle moved beyond a technical barrier and became a business and cultural barrier.

“Kodak invented most of what’s in the digital camera today. They knew this was coming,” he said. “We wanted to give the impression to the general public that digital photography is coming but we’ll let you know when it comes. I think that was one of their mistakes, thinking they could control it by knowing more about it than anybody else.”

The company attempted to bridge the gap in the early 1990s by creating the Kodak Photo CD—sort of a hybrid between analog and digital photography. Though the system ultimately failed for a variety of reasons, Sasson said it allowed him to continue working on digital photography within the company.

Kodak began trying to find niches, where people would be willing to spend more for a somewhat lower quality picture. Photojournalists, for example, would compromise on quality to be able to transfer photos more quickly, Sasson said.

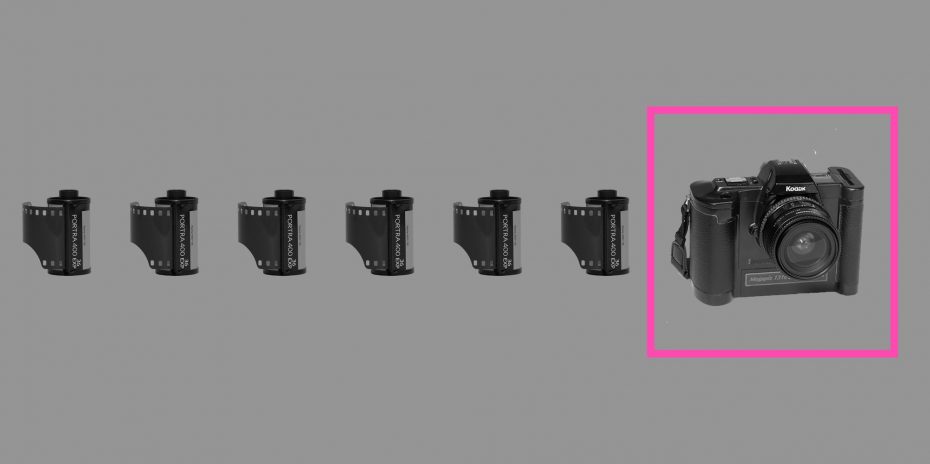

Another opportunity presented itself when Apple approached Kodak in the early 1990s to develop a digital camera connected to computers. That collaboration produced the QuickTake 100. But Kodak was still hesitant about compromising its reputation as a film photography giant and only worked with Apple on the condition that Kodak’s name would not appear on the camera—and that it wouldn’t look like a real camera.

“We always thought if you gave the customer something with superior image quality they would appreciate it. And they did—until they got some more options,” Sasson said. “It turns out they were very happy with a few megapixels because they could see it right away, or they could transmit it to their friend, or they could post it to a social network. People’s value proposition changed with photography. Photography became a casual form of conversation rather than a moment in time. All of that changed and Kodak didn’t react to that. They did dip their toes in all of the right ponds. They just never went in.”