A manned mission to Mars is the stuff of science fiction — but it may not be fiction for long.

The ability for humans to reach and explore Mars beyond the limits of remote-controlled rovers is on the horizon. In fact, it could be a reality in a matter of few decades, according to Dr. Ellen Ochoa, a veteran astronaut and former director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

“People can probably travel farther in a week or two than we’ve traveled on Mars with rovers in 10 or 15 years. Once people get there, the amount of scientific data and exploration will go up exponentially,” Ochoa said. “We could learn a lot more than you can from the rovers.”

Ochoa will explore the possibilities for a mission to Mars on Sept 26. at the event Are We Going to Mars? An Evening With Trailblazers, at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. National Medal of Science recipients Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson and Dr. Sylvester James Gates will join Ochoa, along with Space Foundation CEO Thomas Zelibor.

Though risky, a manned mission could provide an unprecedented level of detail and data of the little known Red Planet.

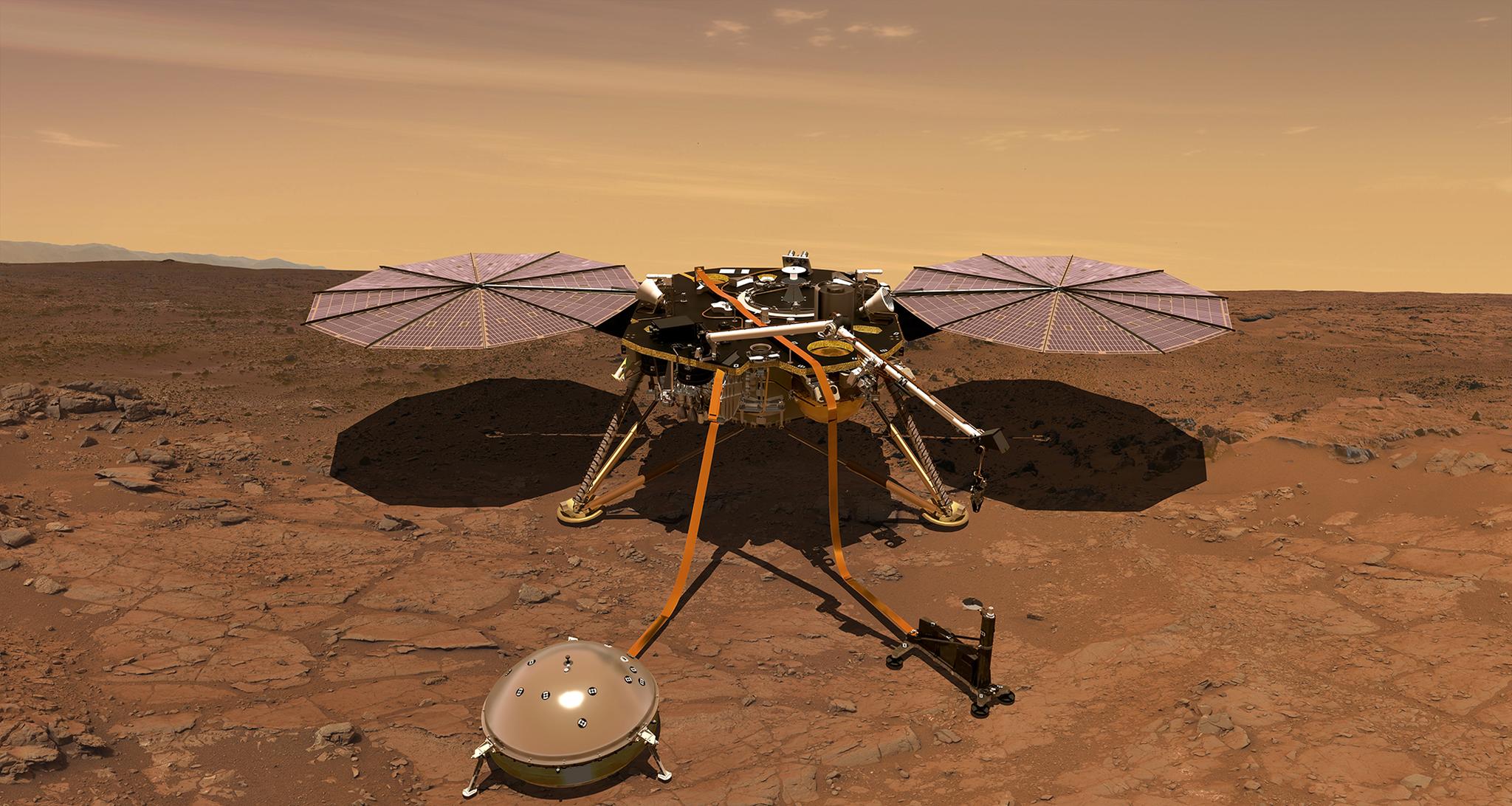

“When you’re getting a rover around on Mars you have to plan very specifically,” Ochoa said. “It is moving at extremely slow speeds. You want to make sure that it doesn’t run into any problems. The whole time rovers have been on Mars they’ve gone just a few miles.”

Jackson, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute president, noted the institute is looking at other ways to improve the efficiency of Mars rovers — without humans. The Rensselaer Artificial Intelligence and Reasoning Laboratory is working to program self-consciousness into robots.

“When one thinks about the Mars rovers becoming sentient — sentient robots — as a precursor to humans on Mars, that is very powerful indeed in terms of the things that we might learn.”

Gates, a professor of physics and the co-director of the Presidential Scholars Program at Brown University, said discoveries today could have unknown and enormous impacts on future exploration.

Gates pointed to the electron as an example. Today, scientific understanding of the electron allows apps and computers to be ubiquitous technology. But until 1891 the mainstream scientific perspective dismissed that there was anything smaller than an atom. But even once George Johnstone Stoney discovered the electron, it took about 200 years for that information to become the devices that many cannot live without today.

“The first person who will know if it is possible to build a starship will be someone who is working on the equations of the kind that I work on,” Gates said of his research to understand the universe at the very smallest levels. “That’s why people like me do this.”

“Just like Stoney could not have imagined a computer, there is no way to actually know what this stuff is going to be good for in the future,” Gates added. “You just know that it is more information. We humans, when you give us information and give us some time, we usually can figure out how to turn information into something that benefits humanity.”

Jackson added that her “generation was captivated by the space race and the endeavor to put a human on the moon,” and hopes Mars can play that same role for a generation of young people today.

The excitement surrounding space exploration and overcoming the challenges of exploring Mars has reinvigorated the industry and interest in the field, according to Zelibor, which he hopes will inspire young researchers and engineers to make a Mars mission possible.

“I’ve been around a long time and I haven’t seen this much excitement about the space industry since the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he said. Jackson echoed, noting the original space race played a key role for many scientists and it bolstered STEM education.

“After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in 1957, you could say there was a kind of sense of panic in the U.S. that we might be falling behind scientifically and militarily,” Jackson said. “There was a tremendous emphasis placed on science and mathematics education in the public schools, and these were fields in which I excelled.”

But as a black woman Jackson faced significant barriers that keep many women and minorities from STEM careers.

“[As an undergraduate] I had a difficult moment there when I did seek the advice of a distinguished professor about majoring in physics. I had the highest grades in his class but his advice to me was that colored girls should learn a trade,” Jackson said.

“I was pretty young and needless to say I was hurt … but I chose to excel,” she added. “Fortunately, the world has grown up since then some.”

But Gates, as a black man and father, still sees those biases at work. His daughter is a graduate student, also studying physics.

“Some of the things that worry me are how difficult it is for young women to continue to have an interest in science when lots of people around them tell them they shouldn’t. I saw that as my daughter grew up. That bothers me,” Gates said. “It bothers me when African Americans get all kinds of messages that you should not be doing this thing,”

Ochoa added that because NASA exclusively selected astronauts from Air Force pilot applicants, space was off limits to women until 1978.

“Women weren’t allowed to be pilots so there was no possibility for women to fly,” she said until NASA expanded its application pool to mission specialists, who did not have to be career pilots.

Jackson calls this a “quiet crisis” because “In spite of the progress we’ve made, [we are drawing] sufficient numbers of women and underrepresented minorities into science,” Jackson said. “I’m hoping space exploration and a challenge of having humans to go to Mars will inspire more young people to envision themselves in these professions, and that the actual endeavor to do that will open up avenues and opportunities for them.”