Football has a concussion problem — and helmets are to blame, says safety expert Dr. Dean Sicking. “They are so poorly designed.”

In 2017, the National Football League documented 291 diagnosed concussions, throughout the preseason and regular season games and practices. For the five years prior, between 212 and 279 concussions were diagnosed each season.

Concussions are increasingly linked to diseases, including dementia, Alzheimer’s, depression and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — all of which have been found in the brains of retired football players and have cast a shadow over America’s most popular sport.

But, according to Sicking, we don’t understand enough about how football blows translate into concussions. There is limited data on the player-to-player impact in football, leaving researchers without enough information to solve the problem.

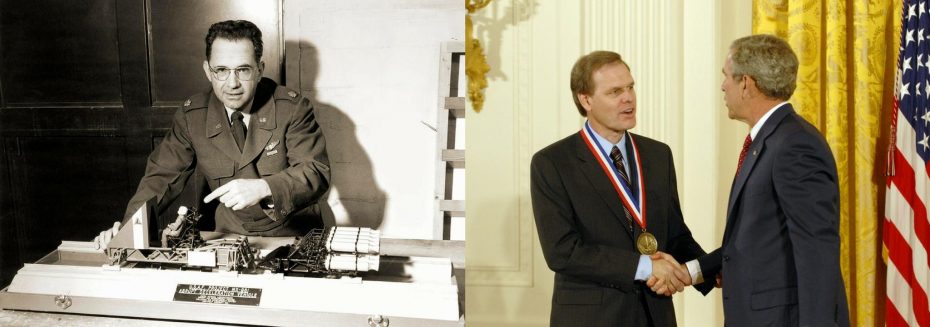

Sicking is best known for developing roadside and racetrack safety barriers that dissipate the energy of high-speed crashes, preventing injuries and saving lives. This work earned Sicking the 2005 National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

“The measure they are using for risk of concussion is not very accurate,” Sicking said of the NFL and helmet manufacturers. “They are using the wrong test and the wrong measurement and the wrong indicator. Three strikes and you’re out.”

The measurements and tests currently used in helmet development tackle a different problem.

Before concussions, football players faced another danger on the field: skull fractures. Between 1961 and 1970, from the sandlot to the professional level, there were 244 football related deaths. Among those fatalities, 73.4 percent resulted from a cerebral hemorrhage, and 16.4 percent resulted from cervical spinal cord injuries, according to findings from Dr. Robert Cantu, a Boston University School of Medicine clinical professor of neurology and neurosurgery.

“That was a horrible thing because skull fractures are very serious,” Sicking said. “So they set about figuring out how to solve that problem.”

Studies at that time involved testing of cadavers in automobile crashes and testing of cadaver wearing helmets.

“They concluded if they could keep the peak load on the helmet below a certain level, a severity index of 1,100 [pounds of force], they just about could eliminate skull fracture,” Sicking said.

After a few years, with improved helmets protecting players from the force that causes a skull fracture, “they wiped out” the problem, Sicking said.

“But ever since then the problem has not been skull fractures. It’s been concussions,” Sicking said. “But no one has reorganized that study of helmet performance for concussions.” And improvements in the equipment “stalled out.”

“They have this measure of risk for skull fractures, [but] they are using that as an indirect indicator of concussions,” Sicking said. “The indicator for risk of skull fracture has got little to do with the indicator for risk of concussion,” because a concussion can occur from impacts that are not forceful enough to cause skull fractures.