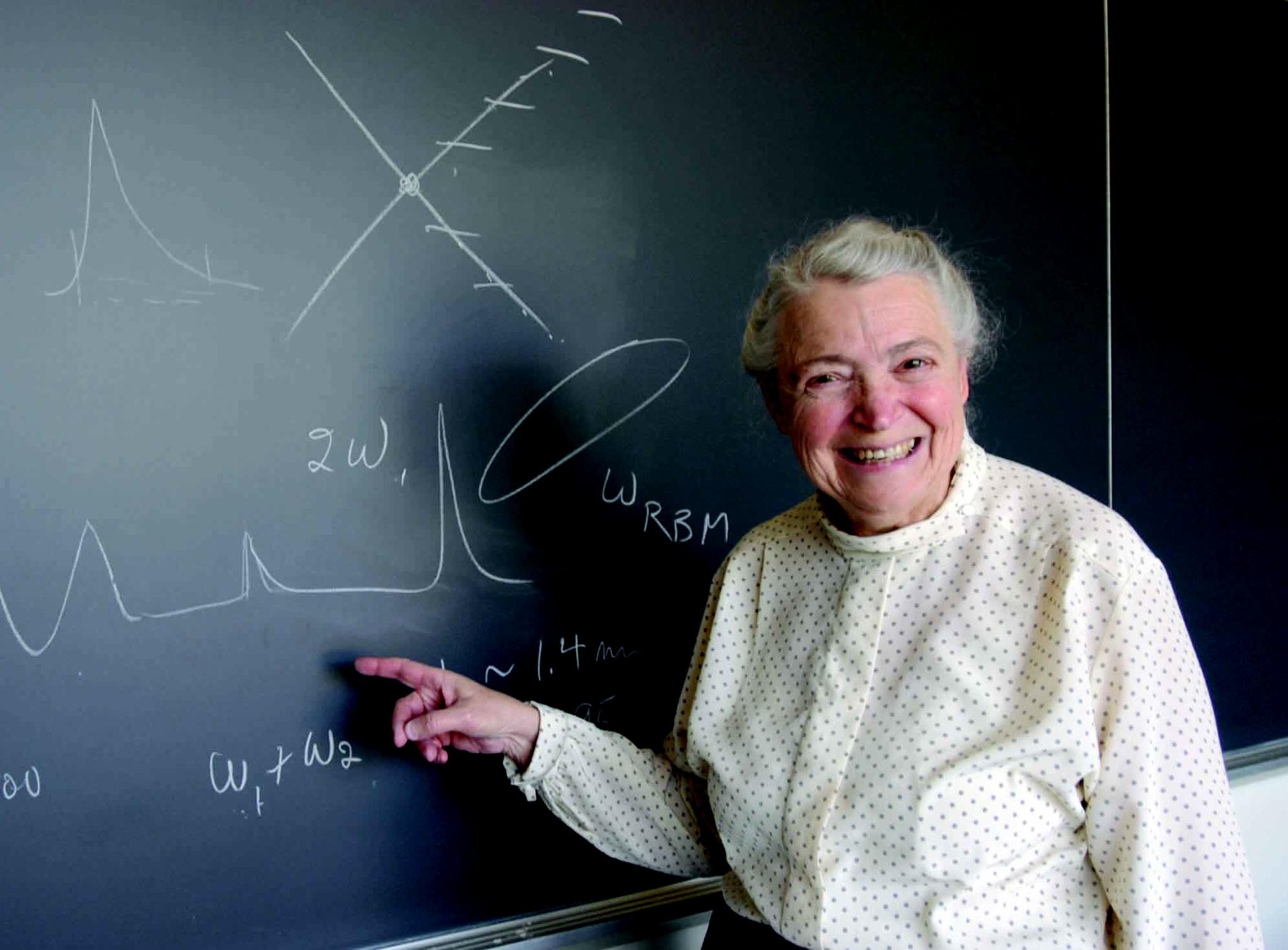

In physics fields, Mildred Dresselhaus is known as the “Queen of Carbon,” but you might not glean the level of scientific royalty by speaking with a woman entirely modest about the list of accolades she’s stacked up over the last five decades.

“I was always astonished that I was selected for these awards,” she says. “They happened, and the recognition makes you think that maybe you’re doing something interesting.”

Her work over the last 50 years hasn’t just been interesting, but groundbreaking. Dresselhaus’s research with carbon paved the way for certain kinds of nanotechnology.

Upon presenting her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom two years ago, President Barack Obama went so far as to say she’s among the innovators who have “changed our world.”

“Growing up in New York during the Great Depression, this daughter of Polish immigrants had three clear paths open to her: teaching, nursing, and secretarial school. Somehow she had something else in mind,” Obama said. “She became an electrical engineer, and a physicist, and rose in MIT’s ranks. She performed groundbreaking experiments on carbon and became one of the world’s most celebrated scientists. Her influence is all around us, in the cars we drive, the energy we generate, the electronic devices that power our lives.”

Since beginning her career in physics at Hunter College in New York in 1951, Dresselhaus has gone on to earn the National Medal of Science in 1990, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014 – the highest honor bestowed to a civilian – and the IEEE (formerly the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers) Medal of Honor last year, among many others.

But after all of the recognition of her tireless efforts toward advancing science, she remains humble, and committed to her original love of teaching – she continues her work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology today, at the age of 85.