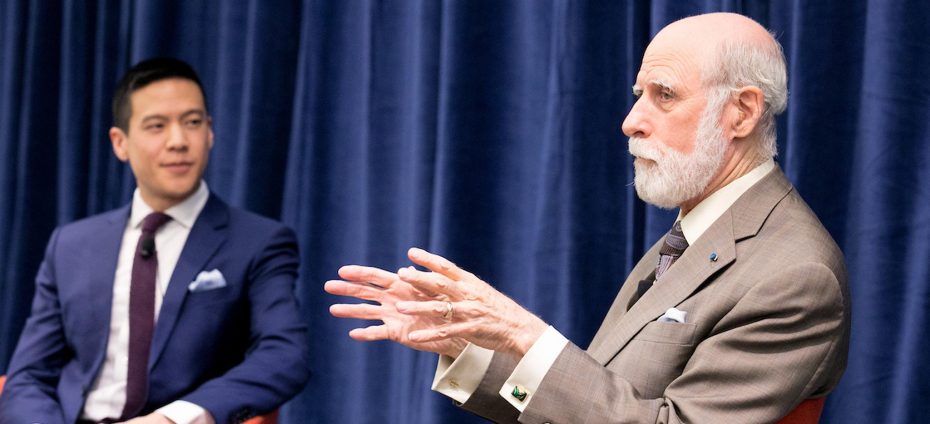

Taking risks is key to unlocking innovation — at least according to one of the co-creators of the internet, Vinton Cerf.

In the 1960s, Cerf and electrical engineer Robert Kahn began exploring a better way for computers to communicate. Decades of research and implementation led to the internet many rely on every day, earning Cerf the 1997 National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

Cerf will discuss the untapped potential of the internet, and its growing pitfalls, with Washington Post technology reporter Brian Fung on April 5 at the National Science and Technology Medals Foundation event “An Evening With Vint Cerf,” at the Georgetown University School of Continuing Studies.

“I see enormous value and at the same time potential risk,” Cerf said.

“Young people … should not feel fettered by the conventional wisdom,” he added. “Sometimes ideas that may seem crazy — to current thinking — are not as crazy as they may sound.”

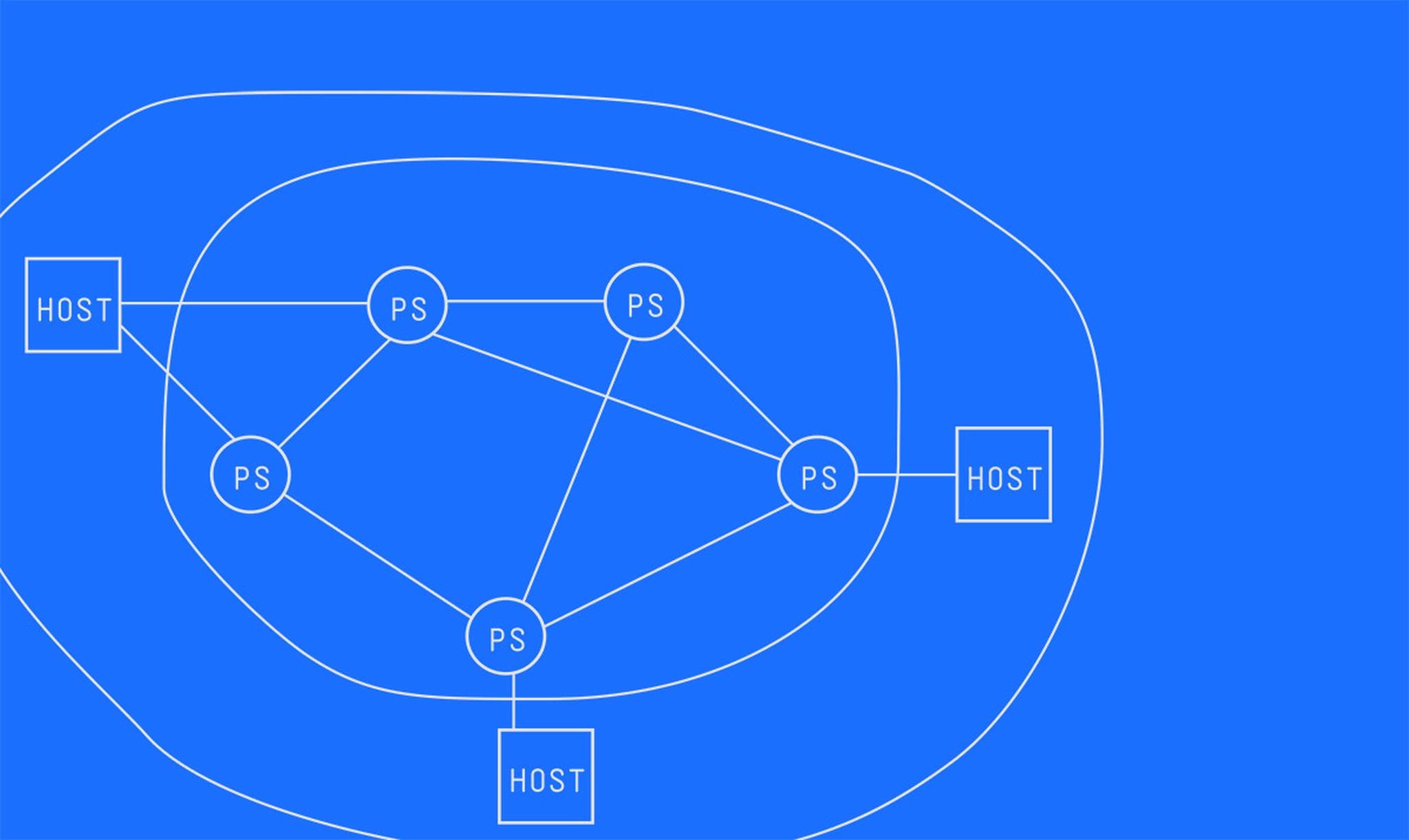

The internet is based on a technology called packet switching, which was viewed by the telecommunication world as “an infeasible and unworkable method for computer communication.” Packet switching allows a message to be transmitted from one place to another by breaking it down into several pieces of data sent independently.

“Packet switching was considered to be a very speculative technology unlike the telephone system, which had been around for a hundred years,” he said. “A lot of people were very skeptical that it could possibly work. The conventional wisdom was that we could use the same technology as the telephone system.”

“It turned out to be an incredibly successful technology and fundamental to all computer communication,” Cerf added.

The success of packet switching led to a more ambitious project — the internet.

“[We] said let’s see if we can take an unlimited number of packet-switch networks and interconnect them in a way that looks uniform,” he said. “When Bob Kahn and I did the original design we basically gave it away, saying if you can build a system that behaves this way then you should be able to connect with other similar systems. We hoped this would grow in a very organic way, which is exactly what has happened.”

Connecting two far away places is what drove Cerf to pursue this technological innovation.

“I have been motivated by this potential to make things happen at a distance,” he said. “I was completely beguiled by the idea that you could create your own universe by programming it and that it would do what it told you to do. You could do something Los Angeles, and something would happen in Boston.”

Improved communication and information flow created a new kind of accessibility for people with disabilities, like Cerf who is hearing impaired.

“One of the things that attracted me to networking was electronic mail because that was easier for me to use than telephone calls and conference calls,” he said. “You could read what people were writing. You had precision. You didn’t have to ask people to repeat themselves. Electronic mail turned out to be a tremendously valuable and important communication medium for me.”

Cerf calls assisted technology a “very powerful enabler,” noting there is still great room for improvement and innovation to empower people with impairments.

“We should be insisting that our computer-based systems be increasingly easy to use for people that have to overcome various disabilities,” he said.