As you walk to meet a friend for dinner, a fitness tracker measures your moves, uploading personal data about each step along the way.

You forgot your wallet, but you don’t think twice.

With the tap of a button, you reimburse your friend through a peer-to-peer payment website, which links to your savings account.

For a lift home, you use a ridesharing app, which – thanks to information you’ve provided – knows exactly where you live.

“We want everything to be interconnected. We want to be able to do everything from our iPhones and tablets,” said Michel Cukier, director for the Advanced Cybersecurity Experience for Students (ACES) at the University of Maryland, College Park. “That adds another level of risk.”

Launched in 2013, ACES is the nation’s first undergraduate honors program for cybersecurity. For graduates, job prospects are good – almost too good, in fact.

“Companies are begging for cybersecurity experts,” Cukier said.

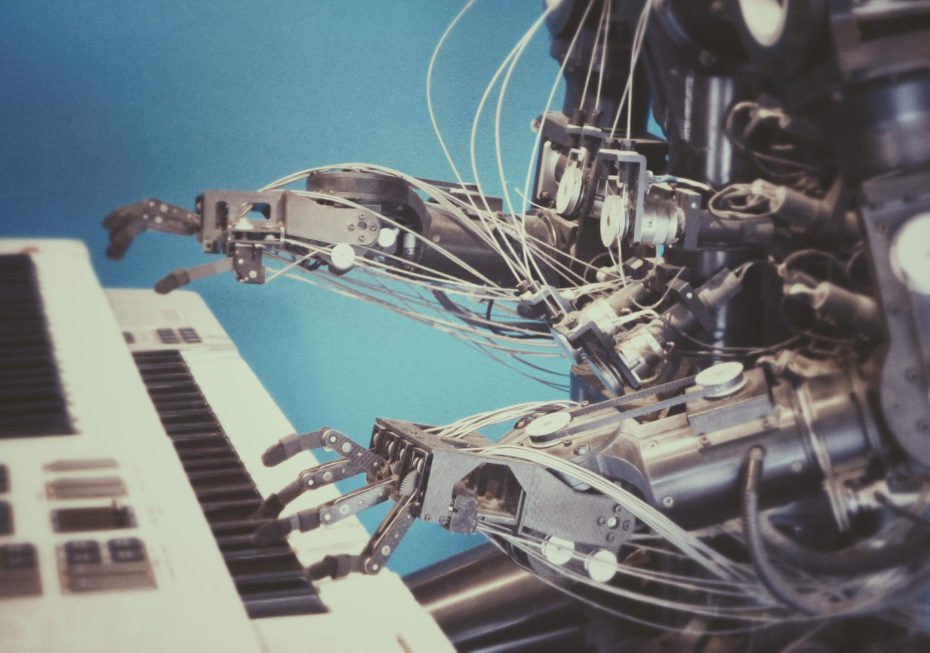

The so-called “Internet of things” – a term used to describe our network of everyday objects with Internet connectivity – is a hacker’s smorgasbord where our identities and national secrets are on the menu.

Nearly 600,000 cybersecurity incidents were reported to the Department of Homeland Security in 2014.

New threats emerge faster than talent can be developed to stop them.

More than 209,000 cybersecurity jobs in America are unfilled, with job postings in the sector increasing 74 percent over the last five years, according to a Stanford University study using Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

A 2014 report from Cisco paints a more dire picture, estimating 1 million unfilled cybersecurity jobs worldwide.

Without action, the shortage will escalate, experts say.

Demand for cybersecurity professionals is expected to surge globally to 6 million open positions – but only 4.5 million qualified applicants – by 2019, according to Michael Brown, CEO of Symantec, one of the largest providers of security software.

Cybersecurity has become a national priority so critical that the White House, building on past efforts, launched an initiative in February 2016.

The proposal, which would increase federal cybersecurity funding by more than a third, includes modernizing IT across the government, investment in cybersecurity education and the establishment of a commission of thought leaders.

This need for talent, however, isn’t as sudden as it might seem, said Anupam Joshi, director of the Center for Cybersecurity and Cyber Scholars Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

“We’ve been hearing for 5, 6, 7 years that we’re not putting out enough people with a skillset in cybersecurity,” he said.

UMBC is a hotbed for cybersecurity talent with more than 1,000 graduates working at the National Security Agency, Joshi said.

While “cybersecurity” is the latest buzzword, the concepts these students learn – keeping data and information out of enemy hands – has existed for decades.

Take, for example, the work of Solomon Golomb, recipient of the 2011 National Medal of Science.

Golomb, who died in May, is best known for inventing mathematical games that served as the inspiration for Tetris.

But it’s his work with cryptography that helped develop early concepts of information security.

Trained as a mathematician, Golomb became fascinated with how algebra, specifically a phenomenon called “nonlinear shift registers,” could be applied to communications.

A shift register, which can be used for cryptographic ciphers, is a transformation of ones and zeroes in which the order of numbers shifts with each repetition.

Hired by the military in 1956, Golomb showed how this tool could be leveraged to create algorithms to secure communications signals.

In his famous list of “Don’ts for Mathematical Modeling,” the tenth catchphrase rings eerily true for the world in which we live:

“Don’t expect that by having named a demon you have destroyed him.”

But when it comes to destroying any evil force, knowledge is power.

“You don’t solve these problems immediately with an unskilled workforce,” said Margaret Leary, director of curriculum for the National Cyberwatch Center, which develops educational standards for cybersecurity.

Leary also heads Northern Virginia Community College’s cybersecurity program, which offers an Associate of Applied Science degree with 49 credits in IT.

The program’s enrollment has surged from 49 students at the end of the Fall 2014 semester to more than 750 in April.

An AAS can be transferred to a four-year institution, where, Leary said, programs often put policy over practicum.

“Training is a dirty word,” Leary said. “But you can’t write the policy unless you understand the technology on which the policy is being written.”

The same schools, she said, tend to put cybersecurity in their computer science program – another flaw in the system.

“The employers don’t understand the difference between computer science and IT,” she said. “Computer science is the creation of technology. IT is the application of technology to meet a business need.”

With this in mind, Leary, who also consults for the government as a security assessor, often recommends re-training for personnel.