Depositing checks to bank accounts. Scanning QR codes and barcodes. Skype. FaceTime. Snapchat and Instagram. And of course, selfies. Digital cameras have become integrated into daily life for much more than just photography.

But the revolutionary piece of technology was almost quashed before making it to primetime, according to the inventor of the digital camera, Steve Sasson, a recipient of the National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

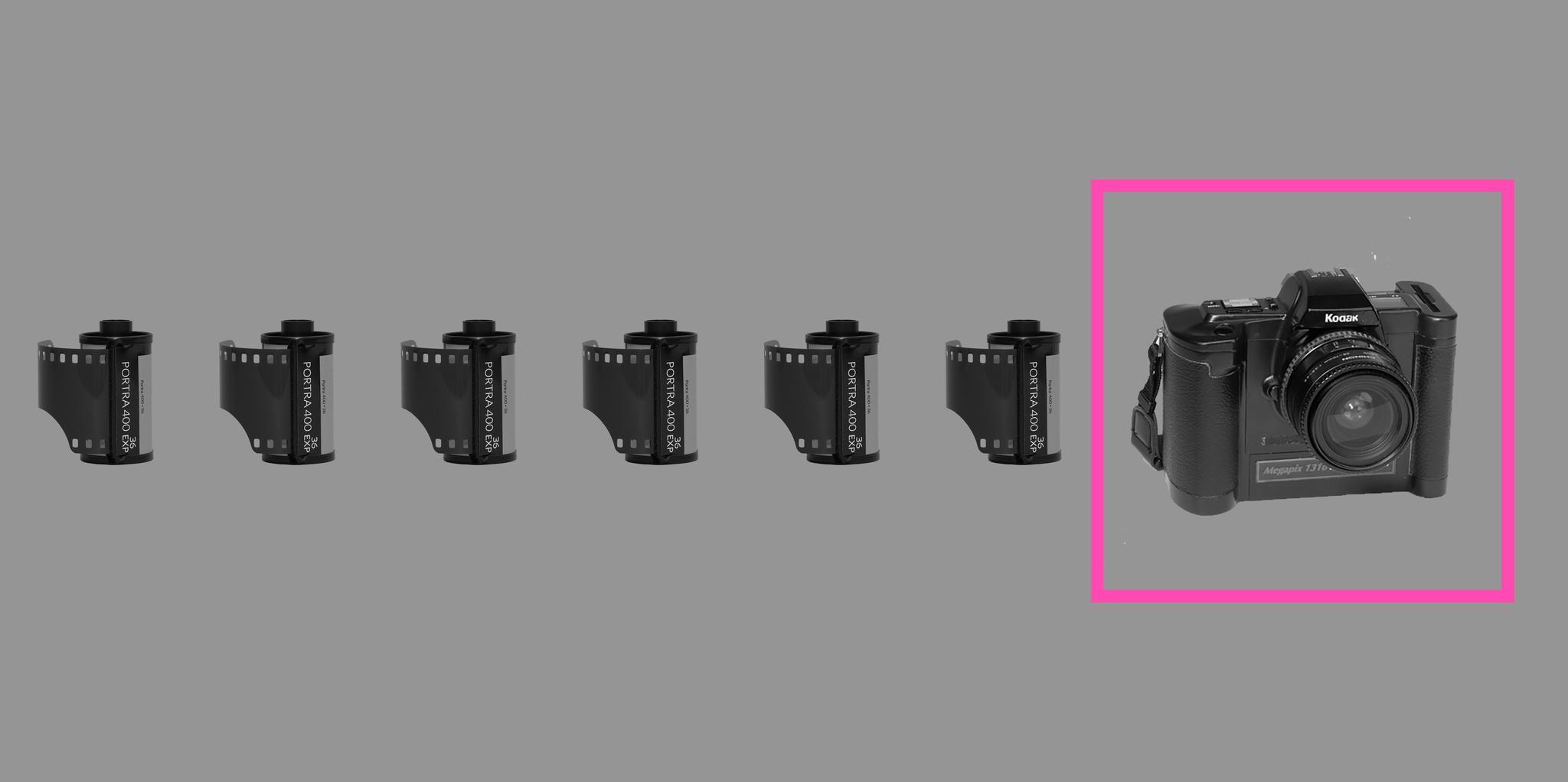

Sasson, who spent the majority of his career working for Kodak and fine-tuning his digital camera prototypes, says the company initially was not too keen on the idea of moving away from analog photography. It made sense — Kodak made its fortune from selling film. Why would anyone want to see images — lower quality images, at that — on a screen?

Not only were the images grainy, but the process was tedious. The first digital camera prototype, which Sasson developed as a side project in 1975 as a 20-something electrical engineer looking to fill time, took more than 20 seconds to develop an image. The image then had to be transferred to a cassette tape and displayed on screen detached from the camera itself. It weighed eight pounds and could store less than one-tenth of a megapixel — a far cry from the cameras we have today.

“My idea was simple: I’d walk into the conference room, take their pictures, and show it to them on a TV set right there,” Sasson says. “We did that, and I thought people would ask me all kinds of questions about how I did this. They didn’t ask me any of that stuff. What they asked me was why. Why would anybody want to do this? What’s wrong with regular photography?”

A blog from the Obama White House illuminates the impact Sasson’s work has had. During the National Medal of Technology and Innovation ceremony, “As Dr. Sasson and the President stood alongside each other, the sound of hundreds of digital camera-clicks filled the room,” the blog post said. “The resonance of the moment was not lost on the President, who playfully pointed to the bank of photographers. ‘This picture better be good,’ he quipped.”

President Barack Obama described the process that Sasson and many other scientists and inventors have gone through, saying “every day, in research laboratories and on proving grounds, in private labs and university campuses, men and women conduct the difficult, often frustrating work of discovery.”

“It isn’t easy,” he said. “It may take years to prove a hypothesis correct — or decades to learn that it isn’t correct. Often the competition can be fierce — whether in designing a product or securing a grant. And rarely do those who give their all to this pursuit receive the attention or the acclaim they deserve.”

That was the case for Sasson. After presenting his initial prototype in 1975, no one tried to stop him from working on the project. So, he continued to work for over a decade to make it something desirable for consumers.

“I was probably the right person to be doing that. I was 25 years old; I had no reputation to protect. I was just excited about the technology. I was excited about the opportunity. I wanted to build this cool camera that didn’t use film. It occurred to me a lot of people might not like that, but I just thought it was so cool, how could [I] ignore the possibility?” he said. “Not one of those really smart people could ever stand up and prove to me that my vision would not eventually happen. There was no law of physics, no law of entropy or anything that they could say it would never get there.”

Sasson says he was initially drawn to science due to his natural curiosity with how things worked. As young as ten years old, Sasson was putting that curiosity to use with a neighborhood friend.

“We started trying different crazy things, and we migrated more toward electronics than chemistry because with chemistry we started blowing things up and got in a lot of trouble,” Sasson joked.

After the two set off a thermite explosion in Sasson’s family garage, his focus turned toward electronics.

“We migrated toward electronics, at least I did, because it was action at a distance. You could create a signal and affect something far away. That was sort of a cool idea,” he said.

Throughout his childhood, Sasson said he collected parts in Brooklyn, where he grew up, as neighbors threw out television sets, radios, and other parts.

“I would drag these things home and take them apart,” Sasson said. “When I got electronic projects I tried to do, I would use those parts.”

Sasson continued pursuing his interest in electronics and inventing at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), where he studied electrical engineering as an undergraduate and graduate student.

There, Sasson had two professors who he says sparked his sense of ambition. During his first semester, he took a physics course taught by Robert Resnick, a world-renowned physics educator.

“I was blown away by how elegantly he solved problems that I had worked on for hours – he never had notes,” Sasson said at an event at RPI in 2016. “I was so inspired by his elegance and ease. He taught me to look at the principles, find out what you know, and go after what you don’t know. I carried that with me.”