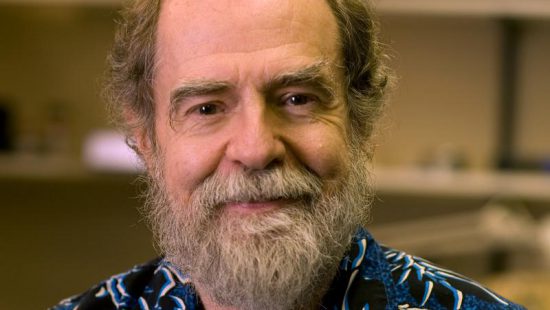

Peter J. W. Debye never liked an easy answer. “If a problem is clearly stated, it has no further interest to the physicist,” he said.

Hungry for knowledge, the Dutch-American scientist concerned himself with the structures of atoms and molecules – the state of matter, in other words.

His early experiments focused on dipole moments, drafting equations to quantify the uneven distribution of positive and negative charges in a molecule.

The units of measurement used to quantify this activity are called “debyes,” in his honor.

In 1915, Debye made a revolutionary conclusion about matter, proving that arrangements of atoms are never random and that perfect crystalline structures are not required for the diffraction of X-rays.

His mathematical equations – used to calculate anything from heat capacity to vibrations on the molecular level – laid the foundation for physicists to come.

“Mathematical physics is in the first place physics,” he said, “and it could not exist without experimental investigations.