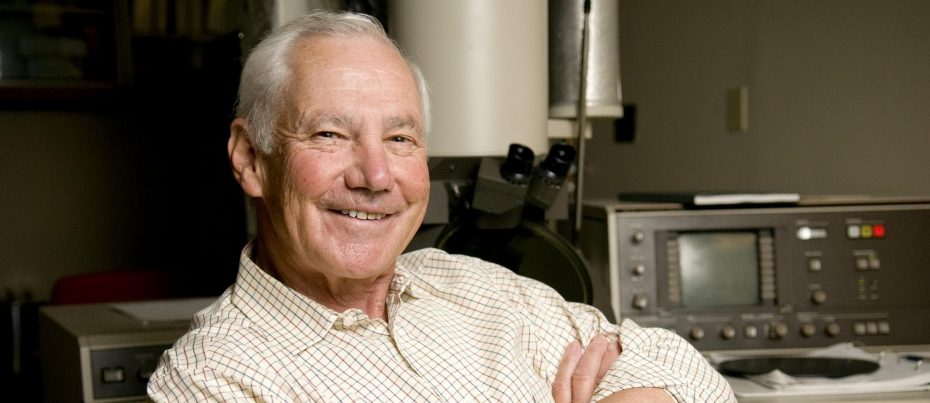

In the 1950s, a medical technologist collected stool samples from surgery patients, encapsulating the frozen feces into pills for ingestion during recovery. The human digestive tract hosts about 1,000 species of microorganisms needed for healthy digestion. Stanley Falkow believed so-called “fecal reconstitution” could repopulate these gut microbes, typically killed off by post-surgery antibiotics. The experiment, ahead of its time, angered a hospital administrator, who – upon realizing Falkow fed patients their own feces – fired the him on the spot.

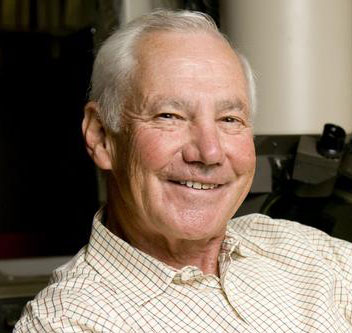

“It’s a repulsive thought,” Falkow, an emeritus professor at Stanford University School of Medicine, told the New Yorker in 2014, “and people are still repulsed by it.”

Through his research, Falkow became an early advocate of the “fecal transplant,” a process of introducing gut bacteria from a healthy person into a sick person’s intestines. Later, Falkow’s “molecular Koch’s postulates” offered an explanation for how genes in these microorganisms contribute to the spread of disease.