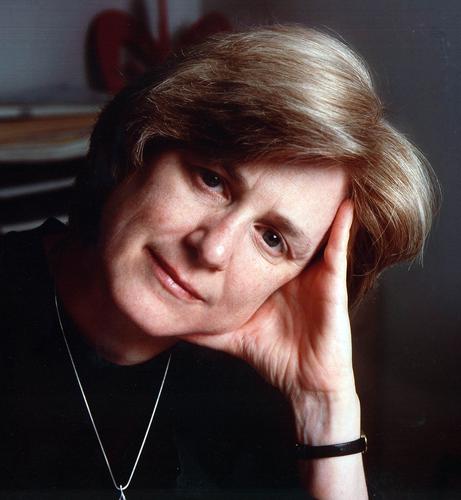

As a teenager, Mary-Claire King watched her best friend die from a kidney tumor. “I always hated cancer,” the geneticist said in 2004. “It was a bad thing and I wanted to fix it.”

In 1990 – after nearly two decades of researching families plagued by breast cancer – she did just that, scientifically proving a hereditary link once shrouded in skepticism.

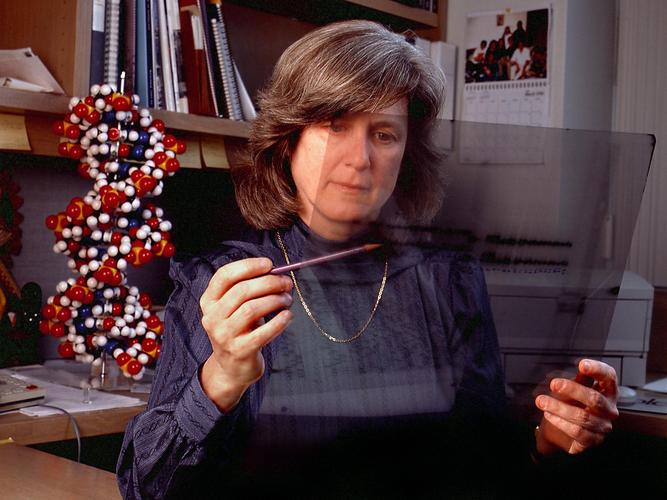

With her team at University of California, Berkeley, King discovered the “breast cancer gene,” called BRCA1. She later furthered this research with the identification of BRCA2, another cancer-causing mutation.

Together, BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancer cases. Today, these mutations can be identified through a test, which King advocates should be offered to all American women around age 30.

About 1 in 8 of these women will develop breast cancer in their lifetimes.

As a result of King’s research, carriers of BRCA genes can consider preventative measures such as double mastectomy, a procedure known to reduce the risk of breast cancer by more than 90 percent in some patients.