When Walt Whitman said “I contain multitudes” it’s doubtful that he was thinking about his inner microbes. But in the past few decades, physicians, geneticists, and microbiologists have come to see that he wasn’t just right, he may have been understating it. At this very moment, you are home to trillions of tiny creatures. Don’t adjust your monitor or refresh the page, you read that right: trillions. Of microbes. Inside. You.

The Tiniest Big Science

Discovering our Microbial Selves

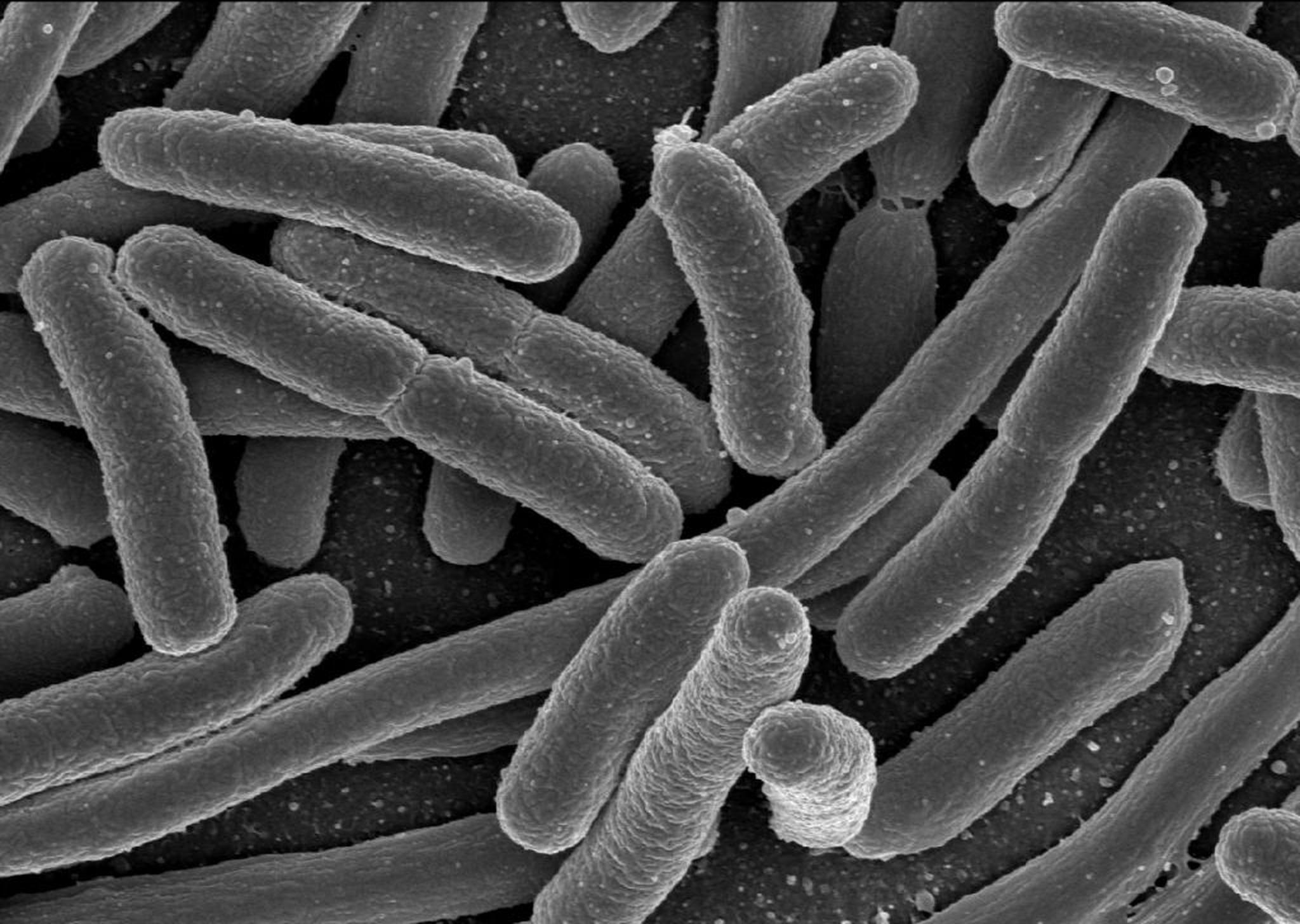

It turns out that human beings are home to a living ecosystem made up of hundreds of trillions of cells—bacteria mostly, but also viruses and fungi—that live on and in us. In fact, it appears that for every one human cell in your body, there are three microbes. You are a petri dish of epic proportions.

Advances in genetic sequencing, such as those invented and popularized by J. Craig Venter, have helped our advance our understanding of which microbes actually make up this community by leaps and bounds. Rapid genomic sequencing has allowed us to understand exactly which microbes live where and how they’re related to microbes both nearby and in other parts of the body.

All told, there are about a pound or two of microbes that have made you their home. They form a vast and complicated inner ecosystem whose complex and clearly crucial workings we are just beginning to tease apart. They’re in our stomachs, on our skin, and all over our teeth. They are everywhere; we’re more microbe than human.

STEP AWAY FROM THE HAND SANITIZER

Don’t reach for the hand sanitizer just yet though. Most of those microbes aren’t making you sick, in fact they are what is keeping you well nourished, healthy, and perhaps even happy.

You are a complex organism and to something as small as a bacterium or virus, you contain many different habitats. Any part of you that is exposed to the outside world—your skin, lungs, digestive tract, nasal passageways, etc—is home to a distinct microbial community.

Because each site is a unique habitat, it hosts its own characteristic set of microbes who are there to perform specific functions such as the digestion of proteins, the warding off of invaders, and even communicating with other bodily systems. Interestingly, not everyone harbors the same microbes in the same places, the microbes of any given habitat seem to be united in their function. In fact, the microbial communities of various body sites are similar across all healthy people. So, the microbes that live on your skin are far more closely related to anyone else’s skin microbes than they are to your own gut microbes.

Though we are still working to uncover the role of each community, what is clear is that those microbes aren’t there by accident. They have carefully co-evolved with us. Just as we provide them a place to live and breed, they provide us with important benefits.

The proliferation of helpful microbes makes it harder for those microbes that can hurt us to gain a foothold. Some microbes help us synthesize vitamins (most notably the Bs and K). Some are even known to assist in the production of signaling molecules like neurotransmitters that communicate with our metabolic and immune systems.

And because microbes evolve much, much faster than us and our genetic information, they can adapt to new situations and new diets much more quickly than we could ever hope to on our own. Their fast evolutionary pace (sometimes a new generation every 20 minutes) provides us with a complement of evolutionary tricks and advantages that we would never be able to acquire should we have to evolve them on our own.

It should be noted however, that this quick adaptation is a double edged sword. That same ability is what allows bacteria to become antibiotic resistant and that is a very threatening thing indeed.

As we’re figuring out, many basic life processes depend on our interior ecosystem. Your gut is home to one of the densest microbial communities ever discovered anywhere. Without the assistance of those microbes many carbohydrates would be all but indigestible. For years, scientists puzzled over the existence of a sugar in breast milk that babies are incapable of digesting. Natural selection would have long ago weeded out such a biologically expensive thing if it had no use! Lo and behold, that sugar doesn’t feed the baby—it feeds the baby’s gut microbes!

THE MICROBES WILL SEE YOU NOW

While we used to think that we needed to eradicate microbes from ourselves in order to be healthy, we’re uncovering a much more nuanced picture. Health, it now seems, is much more dependent on nurturing the good microbes than it is on eliminating the harmful ones.

At this early stage, it is already clear that a healthy microbial community can fend off much larger doses of harmful pathogens than a community that has been disturbed in some way. For example whether or not you’re currently taking antibiotics—which wipe out lots of microbes, not just the harmful ones—could determine whether that mystery meat from the greasy spoon dinner gives you food poisoning or whether you walk away feeling fine.

And it isn’t just traditional infectious diseases that are influenced by our microbes. Diseases as disparate as heart disease, asthma, food allergies, diabetes, obesity, insomnia, and even cancer are now thought to be related to the health, stability, and diversity of a person’s microbial community.

Studies with mice have shown that obese mice who are transplanted with the gut microbes of thin mice lose weight. We don’t understand why exactly, but those experiments show us that our gut microbes go a long way towards regulating our metabolism. It’s not far fetched to believe that other microbes could be responsible for helping to regulate our sleep cycles or moods as well.

Our inner friends also appear to have the ear of our immune systems—helping our bodies distinguish good guys and bad guys, like potential allergens. One line of current research is investigating whether our westernized and somewhat poorer microbial communities could be linked to the alarming rise of allergies and autoimmune disorders. (Both of those afflictions involve the body attacking something it shouldn’t.)

A PARADIGM SHIFT OF MICROBIAL PROPORTIONS

It’s important to realize that there is a gaping difference between correlation and causation. In most cases it’s unlikely that one microbe can cause or cure a disease. But understanding their roles and their needs can help us better treat the whole picture—and avoid causing harm unintentionally. What is clear, is that the microbes all over our bodies are not passive bystanders in our lives. They play an active role is steering the balance between health and disease, and as such could hold many keys for better, earlier, and less harmful treatments.

Drawing on our knowledge of healthy, yet individualized, microbe ecosystems will go a long way towards advancing the goal of creating personalized treatments and preventive care for patients. Already, people like National Medalist Leroy Hood are advancing that cause. Imagine receiving treatment for a disease that is specifically tailored to your own bodily needs—and one that comes without the harmful side effects that come from unintentionally killing the microbes that help keep you healthy. That would be quite a relief!

While it’s still too early to promise cures, a huge shift is already underway in how we think about our bodies and our health. We are not individuals so much as we are communities, self and microbes. That shift may seem minor, but it’s not. We’ve spent decades and decades trying to wipe out microbes—with antibiotics, with poor diets, with antibacterial soap. But we’re learning that the best way forward isn’t all out warfare, it’s careful and considered cooperation.