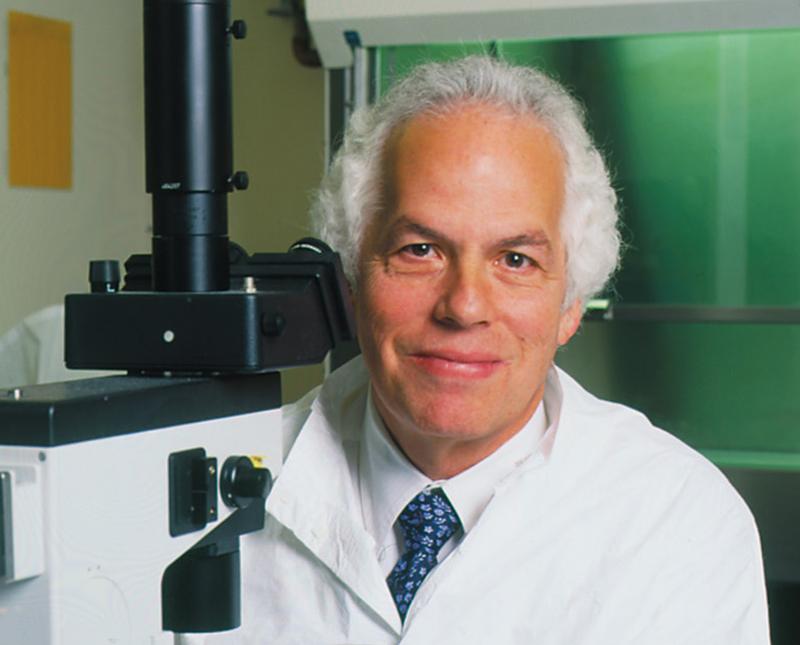

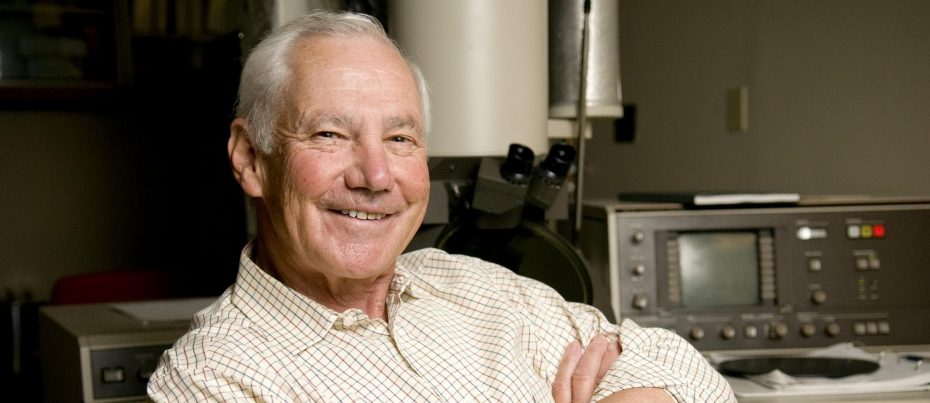

What do you do if you have very little funding, are warned off the topic by colleagues, and are facing considerable doubt from the scientific community? If you’re Stanley Prusiner, you press ahead and eventually discover something wholly new to science.

In 1972, Stanley Prusiner was a resident at the University of California, San Francisco, when a patient with a rare degenerative disease was placed under his care. At the time, the cause of Creutzfeldt -Jakob disease (CJD) was thought to be a kind of slow-acting virus, but no one really knew. Prusiner was determined to chase down the true nature of whatever was spreading CJD and diseases like it.

Eventually, he discovered that it was not a virus at all. Nor was it a bacteria or any other kind of known infectious agent. Instead, it was a rogue, misshapen protein that seemed able to induce other, healthy proteins around it to deform as well. He called his discovery a prion–a combination of the words ‘protein’ and ‘infectious.’ “I couldn’t come up with some clever Greek words,” Prusiner has joked, “because I don’t know any Greek.”

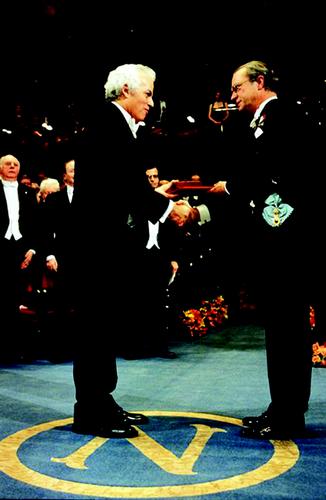

Prusiner’s claim faced a firestorm of criticism, to which he responded with… more data and more proof. By the late 1980s others were coming up with data and experiments that backed Prusiner’s findings. The tide turned, and in 1997 he was awarded a Nobel Prize for his discovery.

Today, prions are thought to be the root cause of diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and CJD (which has been identified as the human form of Mad Cow Disease). There is currently no way to effectively treat prion diseases, but having identified the cause, Prusiner is optimistic that one can be found.