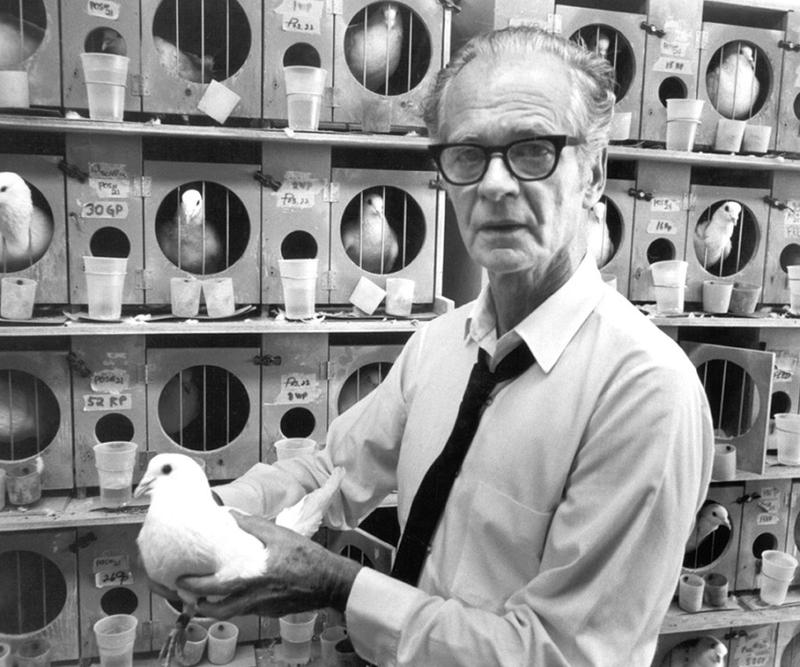

As a rat presses a lever, a food pellet is released. The animal is confined in a sound-proof glass box, limiting distraction from the outside laboratory, as he presses the trigger repeatedly hoping for the same result. While it doesn’t look like much, the “operant conditioning chamber” – nicknamed the “Skinner Box” – has become a staple for studying animal behavior.

At Harvard, B. Frederick Skinner used his namesake invention to prove his thesis: that reinforcement is needed for the learning of new behaviors. In 1948, he recounted this principle in “Walden Two,” a novel about a utopian society that operates on a system of rewards and punishments.

Later in life, Skinner, a behaviorist, dabbled in a variety of tasks, teaching pigeons to play ping pong and building a blanket-less heated crib for babies. His interests, while vast, followed a motto he set for himself:

“When you run into something interesting,” he said, “drop everything else and study it.