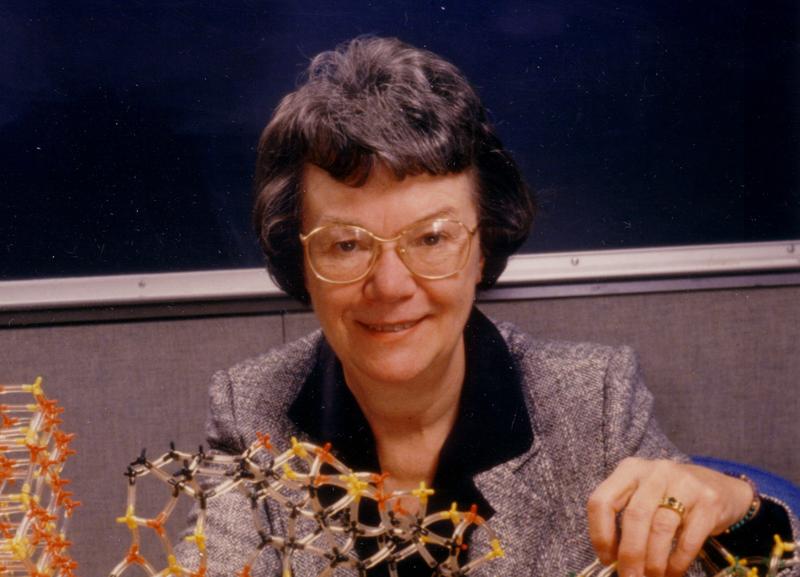

If you’ve filled up your gas tank, washed your clothes, or read about the ongoing efforts to clean up after the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, then you’ve encountered the work of Edith Flanigen.

For almost 50 years, Flanigen has continually innovated and advanced her field of manufacturing compounds known as molecular sieves, or zeolites. Even more laudable is that she did it all at a time when women did not often advance far in the sciences, let alone lead highly successful teams of chemists.

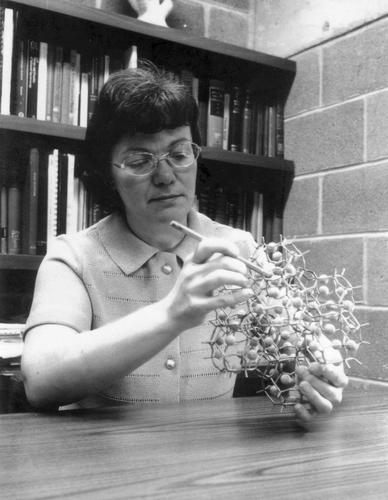

Zeolites are tiny, porous crystals that help separate out and purify chemical mixtures based on the size of their particles. By trapping particles of some sizes and letting others through, zeolites help to sort and separate different molecules.

Though zeolite is a naturally occurring mineral, Flanigen and the group that she led invented over 200 different synthetic versions of the compound that target various particles. They have become part of a billion dollar industry that has a huge range of applications.

Zeolites are commonly used to refine crude oil into petroleum, have replaced environmentally damaging phosphates in laundry detergent, and are even being used to help filter out radioactive material from the water around a Japanese nuclear plant severely damaged by an earthquake and tsunami.

Early success in her career led her to be named head of Union Carbide’s molecular sieve research team in 1968– an extremely rare position of a woman at the time. Flanigen found that most of her male subordinates were supportive, but she quickly won over those who were more skeptical of being managed by a woman. She did so by continuing her brilliant work and encouraging theirs. “I gave them respect,” she said. “Once we worked together and we had successes, they were more excited about the work they were doing…rather than the relationship between the person and myself.”