Of Mildred Cohn’s many qualities as a scientist, her resourcefulness ranks near the top. As the Chemical Heritage Foundation said of her, “when the right instruments were not available, she built her own.”

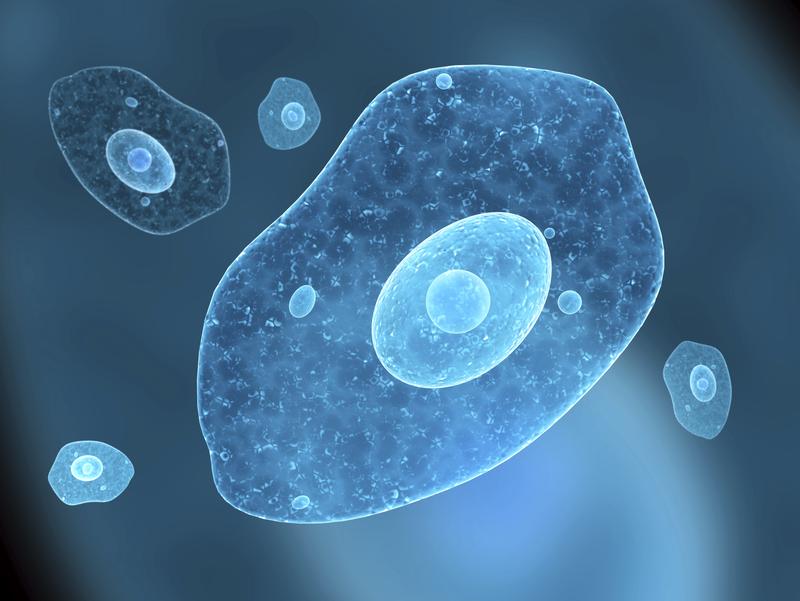

Through the use of high-tech instruments, the foundation said, she transformed the study of enzymes. Her work had numerous other applications. Her pioneering research on metabolic processes, for instance, helped pave the way for the development of the MRI, which allowed doctors for the first time to study the body’s organs and tissues without surgery, and NMR spectrometers.

Born in New York, Cohn’s father was himself an inventor – a skill he obviously passed along to his daughter. Cohn wanted to study physics, but Hunter College didn’t offer it. So she studied chemistry, often ignoring those around her who scoffed at women pursuing careers in chemistry and other sciences.

She pushed back against the gender barrier and earned a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Columbia University in 1938. She had stints as a teacher and researcher at George Washington, Cornell and Washington universities before ending up at the University of Pennsylvania, a post she would hold until retiring in 1982.

By Robert Warren