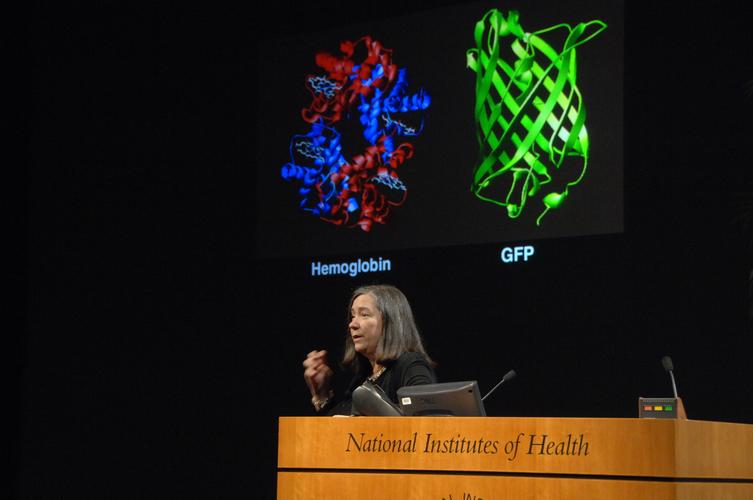

Sometimes it’s the littlest things that matter most. Take for instance the structure of proteins packed inside cells. Thanks to the work of Susan Lee Lindquist we not only appreciate the impact of the origami-like ways in which proteins are folded–we know that harnessing that power has applications in everything from evolution to human disease treatments to biomaterials.

Inside every cell, DNA carries the instructions that tell proteins–the workhorses of cells–how to do their jobs. Each protein must be folded in a very specific way in order to carry out its assigned function and when that process goes wrong, and the proteins don’t fold correctly, it can have terrible consequences.

Cystic fibrosis, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and many other diseases are a result of misshapen proteins wreaking havoc inside the body. Lindquist’s groundbreaking and imaginative experiments have succeeded in reproducing many of the consequences of Parkinson’s in yeast cells–an accomplishment that may yield new and much more effective drugs to treat the devastating disease.

Though she was always fascinated by biology, Lindquist never saw herself going very far in the field. “When I was young, it didn’t seem like the world was open to me,” she told The New York Times in 2007. “When I got to graduate school, Harvard, there were 1 or 2 women professors among the 65 in the biological sciences department. You could not look at that and think you had a chance.” But, she says, the long odds inspired her to take risks with her education and her research–risks that have brought her to the forefront of her field and made her a role model for plenty of young scientists today.