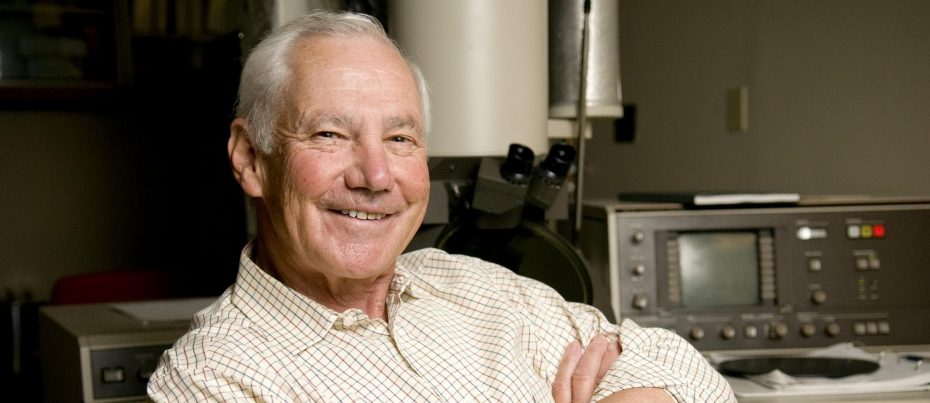

It was the scientific journal cover seen around the world: an average size mouse being dwarfed by this super-sized sibling. Picked up by newspapers from New York to Hong Kong in 1982, the image was seen by millions.

Why? Those mice represented the groundbreaking genetic work of veterinarian Ralph Brinster—proof that it was possible to transfer a gene from one animal into the embryo of another in a way that ensured the gene was not only expressed in the first animal, but in its offspring as well. This work, known as transgenics, has the potential to change fields as diverse as cancer treatment and the production of food crops.

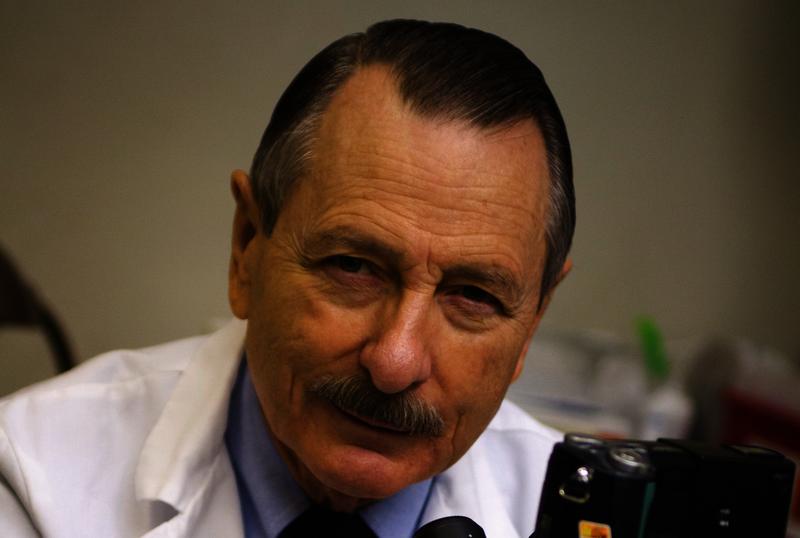

Growing up on a farm, Brinster had ample opportunities to see firsthand how important breeding was and how it passed along characteristics from one generation of animal to the next. Germ lines, a technical name for sex cells like eggs and sperm, are the way that sexually reproducing creatures pass on their genes. In Brinster’s own words, “they are the only cells that biology really cares about.”

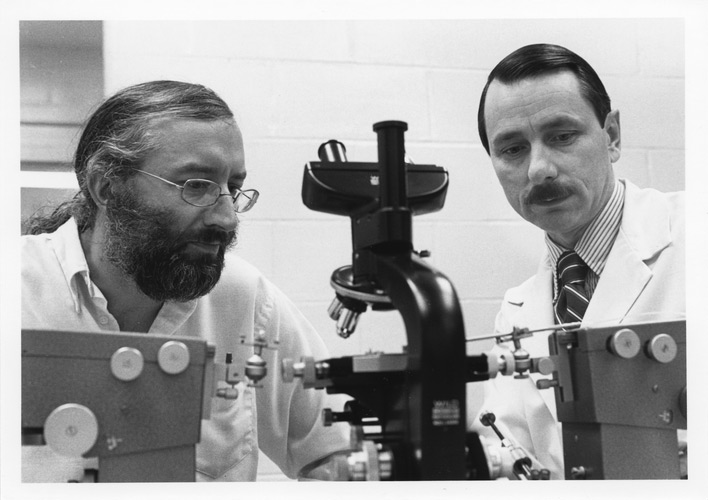

Brinster was the first to develop a way to observe and manipulate these cells and the embryos that result from them outside the body. The method he developed, still widely used today, allowed him to understand more about germ line cells and embryo development—and how alterations of those cells might be possible.

From there, he and collaborator Walter Palmiter went on to refine their revolutionary method of creating transgenic creatures that were able to pass their modified genes on to their offspring. Their creation of a transgenic mouse not only made Brinster the first veterinarian to win a National Medal of Science, but shined a light on how we might one day be able to use genetic therapies to treat a range of disorders like cystic fibrosis and cancer.